NISLab

- Kindle usability

Amazon.com’s Kindle is among several recent attempts to renew the decades-long quest for an electronic book breakthrough in the market. We evaluate Kindle 2.3 International with 6” screen (the small Kindle) based on four months of use since the first International Kindle was released on 19 October 2009. We conclude that a usability breakthrough has, indeed, happened but that the current Kindle concept is highly unstable, sitting between a basically usable novel-reader with some well-defined challenges ahead and yet another all-singing-and-dancing monster.

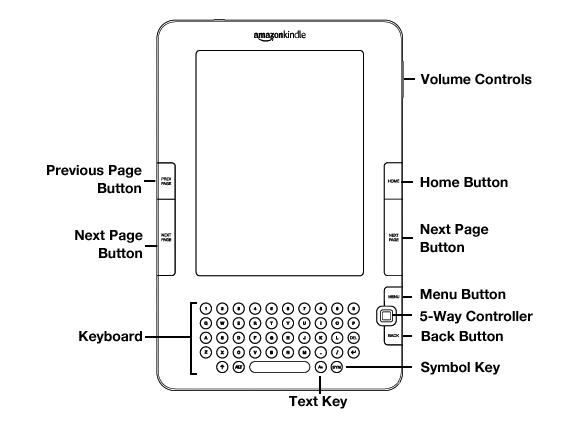

Here is a photograph of Kindle International from Wikimedia Commons:

Kindle, at 13.5 x 20.3 cm (5.3 x 8.0 in), is a bit wider and somewhat taller than the average (closed) paperback novel at, say, 11 x 18 cm. Kindle is a slim (9mm, 0.36"), relatively lightweight (289 g, 10.2 oz) tablet device with simplified standard Graphical User Interface (GUI) functionality as we know it from the PC, and optional audio output.

Input is purely haptic, with much of the functionality of a standard keyboard distributed on the four sides of the contents display, including:

Output is graphic and acoustic.

Graphic output is shown on:

Acoustic output consists of optional:

Customisation is available of font size, words per line, screen rotation (portrait/landscape), text-to-speech settings (on-off, speech rate, male/female voice), and of how to order the contents of Kindle’s local home directory. Font size and words per line customisation does not affect the home directory pages, the menus or, of course, the labels on buttons and keys. This is probably why home directory and menus use a boldface font that is relatively large although considerably smaller than the largest possible font size.

Amazon estimates that the hardware stores about 1500 non-illustrated books on the 1.4GB available to the user. The hardware also has:

Kindle 2.3 supports the Kindle format .AZW which is proprietary, DRM (Digital Rights Management) -restricted and used by books purchased in Amazon's Kindle store. In addition, Kindle supports reading or listening to the file formats: .PDF, .TXT, DRM-free (unprotected) Mobipocket .MOBI and .PRC, Audible (proprietary format for audiobooks) .AA, .AAX, and .MP3 (for music and audiobooks). So you cannot buy, say, a DRM-restricted Mobipocket book and then read it on your Kindle. And unlike almost everybody else, Kindle does not support the open .EPUB standard created by the International Digital Publishing Forum (IDPF). Thus, in the Wikipedia table on e-readers and formats, Kindle is the only one among 16 e-readers which does not support .EPUB. And according to the comparison of e-book readers, only two other e-book brands support .AZW.

The following formats can be converted for Kindle by Amazon: .DOC and .DOCX, .RTF, .HTML and .HTM, .JPEG and .JPG, .GIF, .BMP, .ZIP.

The user guide in the local home directory is generally well-written and detailed. It's long, too, close to half the length of a paperback novel.

Kindle is, first of all, a device for reading e-books. However, it does not merely serve the task of reading an e-book but also, more or less "experimentally", carves out large chunks of the entire - and vast - domain of e-readers in general. So, secondly, Kindle is a device for accessing amazon.com's Kindle Store in order to search, browse, select, buy, and download new books and periodicals or just download these from the reader’s own remote archive at amazon.com. Thirdly, Kindle, which runs under Linux 2.6.10 itself, is free-download GUI software applications that run on Windows PCs and laptops, on iPhone and iPod Touch, Blackberry, and "soon" on Mac OS X. This enables users to access Kindle contents in familiar GUI contexts, seamlessly migrate from one device to another whilst reading on, go to amazon.com via those devices' access to web and email, access the user’s remote Kindle archive, and use Amazon's service for converting text and image files into a Kindle-compatible format. Finally, Kindle includes three so-called "experimental" applications: text-to-speech, primitive uploading of MP3 music to listen to while reading, and a basic web browser primarily for browsing text-based web sites. Web search and browsing does not, however, work on this evaluator's Denmark-based Kindle International. This is, in fact, true in most countries, says Wikipedia.

Kindle does not enable a new type of task to be done but offers a new way of carrying out the age-old tasks of reading books and similar. Paper books and similar are fine devices for enabling these related tasks, so, to conquer the market, Kindle must somehow enable us to do some or all of these tasks better, add attractive new functionality to the reading domain, or otherwise improve the reading experience.

We start with technical issues, not because of having done any systematic technical testing but because it is crucial to understand if this usability evaluation is based on a technically flawless device or marred by technical problems.

Kindle is well-tested technology, and the only technical issue identified during four months of daily use is that, occasionally, the device turns unresponsive to input for some time, such as up to 30-40 seconds, during which the user hits various buttons to try to fix the problem. This never happened when the Kindle was being used exactly by the book but, on the other hand, it doesn’t take hostile testing to make the device temporarily freeze, just a bit of experimental button-pressing. It is not clear exactly what makes it come back to life but no permanent freeze requiring reset was encountered.

We use our reading skills for very many different purposes and in many different contexts. A basic reading task is that of reading a text-only novel for several hours non-stop, then do something else, and then resume reading. With an ordinary paper book this novel-reading task (i) can be carried out with little fatique caused by the reading process itself (as opposed to the book’s contents which may of course leave the reader shocked, breathless and exhausted).

During the reading process, the reader (ii) typically shifts position from time to time, (iii) occasionally leafs back or forward, and (iv) may shift from grabbing the book to putting it down somewhere to read from, and vice versa. With glossy paper and some kinds of illumination (v), the angle of the book page to some light source may have to be adjusted to avoid glare. And if (vi) the book is particularly heavy, some reading positions may be excluded (such as lying on one’s back reading). However, for most readers, there are always several positions left in which unencumbered reading may take place. Finally (vii), novel-reading is ubiquitous, being done in a chair-by-a-table, in the sofa, in trains and airplanes (wireless turned off!), in bed, on the floor, in the gym, on the beach and nearly anywhere else, even when walking, which is notoriously dangerous.

Based on our analysis of novel-reading, we can define the novel-reading test as the test to find out how well an e-reading device enables this task. A device passes the test if, everything considered, it enables the task to be done approximately as well as does a paperback novel or similar.

Arguably, until the current wave of e-book readers came along, no e-reader has succeeded in passing the novel-reading task test. Moreover, if an e-reader that has been specifically designed for meeting this test cannot pass it, this e-book reader probably is not going to survive in the market because we, the large majority of novel readers, will stick to paper books instead.

Let’s see how well our small 6” Kindle fits users doing the novel-reading task.

Impressively, the electronic paper reads like real, non-glossy paper in most but not all lighting conditions. This reduces the visual differences between reading a paper book page and a Kindle page to two: (a) the Kindle screen and (b) the small size of the Kindle page.

The screen reflects light sources in more or less the same way as glossy paper does. This means that it is sometimes necessary to take care to avoid reflected light from the page/screen, particularly when reading by lamplight. This is normally easy to do.

The 6” page works fine for reading as it is. However, a larger page display size is certainly desirable in order to make the Kindle page as large as a standard paperback novel page, improve visual page overview, and reduce the need for constant button-clicking to turn pages. A 6” Kindle page must be turned about three times each time we turn a page in a standard paperback novel which allows us to read two pages before turning the page.

Kindle is best used for reading when it can simply rest in a pair of hands or when you don’t have to hold it in your hands. As soon as you need to grasp the device with your fingers in order not to risk dropping it, like when reading lying on your back or with both elbows on the table in front of you and Kindle up there in front of your nose - you realise (a) that Kindle’s plastic surface is quite smooth and potentially slippery, (b) that your fingers easily trigger page-turning or other functionality since the buttons sit along the two longer edges of the device, or even (c), depending on your finger strength, that a Kindle is far from weightless (but neither is a paperback). However, Kindle's weight is not an issue given the ways it is natural to hold the device whilst reading.

For the same reason that it’s hard to grab the Kindle by one of its edges without pushing a button, key or controller, all buttons, as well as the 5-way controller, are easy at hand for being operated by the thumbs, in particular when the device is resting on the other 2 x 4 fingers and the thumbs are the only ones that are positioned in front of the device. This works even better if the Kindle is wrapped in a protective cover which gives it a bit of extra width and puts the main buttons and controls right around where the thumbs sit in their resting positions.

When Kindle is turned 90 degrees anti-clockwise in order to use the landscape view for enlarging non-text graphics or perhaps being able to read a pdf document, the operating routine that you've acquired for handling Kindle in its upright position goes out the window and things become a bit awkward.

Navigating a novel during basic novel-reading involves: (i) finding where you got to last time in order to go on reading from there, (ii) turning pages, (iii) finding structural points in the text, such as chapter starts, title page or table of contents, (iv) finding a particular passage in the text, and (v) finding a particular illustration, if any.

(i) Navigating - where was I? Kindle always knows where you’ve got to in the novel text and opens, or can be made to open, the text at that point, avoiding the need for inserting bookmarks or remembering page numbers. Still, it’s possible to insert a bookmark as well. Since font size can be customised, page numbers won’t work and have been replaced by unambiguous “locations”, such as “Locations 1293-1303” and “35% [into the book]”, as it says at the bottom of the page in a book I’m currently reading. The notion of locations is quite unfamiliar but most of us probably tend to read novels without worrying much about page numbers, percentages of read and unread text or, indeed, locations except in order to gauge how much is left of the novel we’re currently reading.

(ii) Navigating - turning pages. Kindle has large left-thumb and right-thumb buttons for turning to the next page, and a smaller left-thumb button for turning to the previous page. This works OK and is reasonably easy to get used to.

(iii) Navigating - finding structural points. You can always select “Go to Beginning” [of the book] in the menu, or “Cover” to see the cover, and you can always type in a “location” number to go to, assuming that you manage to remember the number of the location you wish to go to. Subject to publishers’ decisions, only some books have a “Table of Contents” to which you can go from the menu. If a book has a table of contents, it also seems possible to jump from chapter to chapter by simply pushing the controller to the left (earlier chapters one-by-one) or right (later chapters), which is fast and easy. Without these built-in structural stops, moving quickly back and forth in the book by typing in “locations” or simply by turning pages is cumbersome and unrealistic. It is much faster to leaf through a paper book.

(iv), (v) Navigating - finding a passage or illustration. Looking for a remembered passage or illustration by turning pages in a Kindle is many times slower than in a paper book because (a) a 6” Kindle page only contains about one third of the text that’s on two pages of an average paperback even though these two alternatives can be visually scanned equally fast, and (b) turning pages by means of the “prev/next page” buttons takes significantly longer than flipping pages in a paper book, partly because the electronic paper ink must reorganise rather slowly by each turn (page refresh rate is 0.9 s).

Navigating – summary. It is easy to turn pages one at a time whilst reading. However, the 6” Kindle has an overview problem due to (i) the small size of the single page that’s visible at any one time, (ii) the time it takes to move to the next or previous page, and (iii) the fact that some current e-books lack large numbers of structural stops between which one can move by simply pushing the 5-way controller left or right. The only positive news is that most readers may not want to navigate back and forth a lot in the novel they’re reading. Those who do will probably quickly get dissuaded unless they want to really get to work by inserting and using bookmarks, notes and highlights (see below).

We have defined our test basic reading task as being virtually text-only. Even novels of fiction may include a couple of images, maps or other analogue representations, however, typically shown in greytones. In Kindle, such representations are often smaller than the 6” display and some of them are just too small for meaningful use, such as a map that’s too small to read, or a photograph of a group of people that's too small to extract details from. To help readers, Kindle has a one-step zoom function which blows the representation up to full screen size, removing any caption or other supporting context. This helps, of course, but Kindle is still not at all impressive as a device for showing images and other analogue representations. One factor seems to be that the contrast isn't good enough: the grey background is too dark. Another, that publishers market too many books whose illustrations and other non-text graphics cannot be properly displayed on the small Kindle.

This means that there are numerous analogue representations which cannot be usably shown on a 6” Kindle page at all even though they can be quite usably shown on the pages of paper books, especially those which are larger than the standard paperback novel or which use special paper for illustrations. Moreover, if the analogue representations are meant to be used frequently for reference whilst reading, it becomes desperately annoying to have to zoom before being able to consult the representations once they have been located, which, as we have seen, is a problem in itself. That’s why the 6” Kindle is for text-only “paperback contents”, possibly enriched by a small number of low-complexity analogue representations which do not have to be consulted frequently. For reading other kinds of books, the 9.7” Kindle DX is one option and is actually being marketed as better suited for displaying textbooks (quotes Wikipedia). We are not evaluating Kindle DX here, though.

The main issues with basic reading using Kindle compared to an ordinary paperback are:

None of these issues are crucial ones, given the assumption that we are dealing with reading novels for pleasure, which does not require much navigation around the book, and given the fact that there are several perfectly natural and relaxed ways of placing or holding Kindle while reading. Still, each issue is a potential nuisance for the reader and calls for ideas that might improve the reading experience.

It does not seem possible at this point to resolve those three issues together without rather drastic re-design.

Larger screen: My personal favourite is to drop the keyboard to obtain a 35% or so larger screen. I would only loose the Kindle-internal search and note-taking functionality since I prefer to buy new books for the Kindle over my PC and laptop rather than via Kindle’s mobile phone network connection. I would gain an even better novel-reading machine.

Scrolling: To improve overview and fast navigation, it would be nice to have a book represented as continuous and scrollable contents operated via an up/down scroll botton or a touch screen.

Touch screen: If the device were to have a touch screen, current hardware control buttons and keyboard could be replaced by soft on-screen buttons and keys, adding new natural ways to hold and handle the device.

Kindle clearly does pass the basic novel-reading test. Reading text-only novels on a Kindle, page by page and with little long-distance navigation in the text as a whole, is essentially as functional, easy and pleasant as with a standard paperback novel, leaving the reader no less happy and no more tired after several hours of non-stop reading. Kindle is usable as a novel-reading device. As a reading device, it’s not better than a paperback – it’s slightly worse, in fact. Still, for what it is worth, this is what puts the Kindle in competition for making text-only paper books obsolete.

Let's now look at what Kindle offers over and above a basic novel-reading device, i.e., we look at Kindle as an electronic gadget that can do many things which paper books cannot do. We split this topic in two: (i) Kindle’s main difference from a paper book, and (ii) gadget nitty-gritty.

The primary reason why e-books or e-readers more generally, will replace much, if not most, paper reading material more or less completely is that Kindle and, arguably, any competitor that stands a chance of defeating Kindle, allows users to download the material onto the device wirelessly, anytime and in virtually no time: no more book store excursions, no more waiting for them to take books home for us, no more waiting on the book that was ordered over the Internet, no more tree-to-book-page paper processing, no more sending of tons of printed books around the world to publishing houses, booksellers and customers. Partly because of having said goodby to all that, we may hope that e-books will become cheaper than paper books have ever been. And then there will be no more storing of hundreds or thousands of books at home, no new bookshelves, no more moving costs for books, 24/7 book shopping, and you can travel with your library.

Simply put, now that there is usable basic reading device technology, the familiar virtual-over-paper advantages kick in, heralding the demise of the paper novel and probably of other major types of paper reading stuff as well, such as text books that don’t require colour but merely a larger display than that of the small Kindle. Snail mail is going down and so are most other physical vehicles for conveying and storing information - CD-ROMs, DVDs, paper newspapers, paper novels. Paper magazines are being nibbled at as well. With continued smart e-reader development, more will follow - manuals, photocopies, formal letters. And with colour, video and animation, information presentation will change beyond recognition.

Let's see in more detail how Kindle tries to become more than an electronic paper book equivalent. The domain of "e-reading replacing paper reading" is huge and includes countless user tasks that could conceivably be supported by electronic reading devices. Kindle supports the basic task of reading text-only novels reasonably well, and Amazon might have stopped there, just ensuring that electronic novels could somehow be uploaded to and removed from the device. But Amazon didn't. They went at the domain like kids in a candy store, and thus Kindle supports - more or less well, more or less "experimentally" as Amazon says, in more or less complex tandem with networked computers - lots of different tasks. The resulting, implemented e-book reader concept is highly unstable and would seem far from those that will prevail eventually.

The keyboard has two main roles. (i) It symbolises the aspiration that Kindle be not just our preferred novel-reding machine but an all-singing-and-dancing device for reading novels and other kinds of book, periodicals including blogs from Amazon's Kindle store, text and PDF documents, image files, for ordering and re-locating them, for browsing the web and acting as a music center, sometimes in complex cooperation with PCs and laptops. The logic of stopping exactly there is far from obvious. Why not add email, email attachments, social networking, or mobile phone functionality? The keyboard is there already, it's natural to communicate with others about what one is reading, and Kindle cannot do several of the things it does now without more or less cumbersome help from PCs and laptops. For instance, if I want to upload PDF documents directly onto your Kindle, you must modify your Kindle's settings to grant me permission to do so, and I must attach the PDF file to an email sent to your Kindle's remote-archive email address. Or if I want to edit the file called "My Clippings" (supposing I have created one), I must transfer the file to my computer, do the editing, and transfer back the result to Kindle. And MP3 files and audiobooks must be uploaded from a computer.

It is often hard to get things right when carving an application's tasks from its domain. Here's a minimal and conservative, SMALL KINDLE BASIC suggestion that I would be personally happy with, and so might other incarnated readers: use a networked computer for ordering books for Kindle and don’t use Kindle for what else the computer does better, such as web browsing that requires a larger screen. Use the MP3 player for what it's good at and don't turn Kindle into a primitive music center. Use 6” Kindle mainly for reading novels and forget about textbooks and most magazines. Maybe drop the keyboard and thus get a larger page to read from. While the keyboard is still there, mainly use it in emergencies, like when you have run out of novels and have no networked computer at hand. Then do a LARGE KINDLE BASIC like the 9.7" Kindle DX in order to replace non-text-only paper media. And then work at the really interesting stuff: the illustrated e-newspaper and its reader, the e-textbook and its reader, the e-glossy magazine and its reader, the e-everything else reader!

The second role of the keyboard (ii) is for making notes and writing search phrases whilst reading. If you don’t do these things while reading novels, you will do fine as a reader without the keyboard.

The Thesaurus information is mostly there no matter by which word the cursor is being placed, sitting unobtrusively in two lines of text at the bottom of the page and easy to access in full by pressing a button. This is an excellent example of the added value of electronic representation over paper. The only thing that is not obvious is why some basic words or maybe word classes are not being looked up.

Having essentially a small-screen graphical user interface, Kindle is not entirely devoid of typical GUI problems with (i) ambiguous keywords and keyphrases on keys and buttons and in menus, (ii) clueless multifunction buttons, and (iii) absent or misleading context-sensitive help. However, the simplicity of the functionality for supporting reading and the good work done on context-sensitive help means that most readers should be able to figure out and execute much, if not most, of the basic reading functionality that Kindle offers them, which is not bad given the GUI track record. Here are some examples:

As for (i) ambiguity, Kindle has two “enter” keys: down-pressing the 5-way controller and pressing a small key that’s part of the keyboard and bears the angled-arrow “enter” icon. Use of the latter is limited and explained in context-sensitive help whereas the uses of the former are many and diverse and only partly explained in context-sensitive help. The “Text [settings] Key” is labelled “Aa” and turns out to open a menu whose contents makes you wonder about the key’s name and labelling.

As for (ii), multifunction buttons, the power switch on the top edge of the device (a) (un-)pauses the display, (b) switches it on and off and (c) resets the Kindle. While this is relatively simple (but not intuitive), the multiple, context- (state- or mode-) dependent effects of pushing the 5-way controller in its five directions are not simple at all. This is where context-sensitive help is really needed.

As for (iii), context-sensitive help is rather good in Kindle, providing adequate guidance for what to do in the second step of several two- (or more-)step activities, once the user has taken the first step. The first step may in many cases be taken by clicking on a menu item, such as “Add a Bookmark” or “Search This Book”, but not in all. For instance, if a user never pushes the 5-way controller toward the bottom of the page whilst Kindle is in book-reading mode and thus manages to make visible the cursor and an explanation of a word or phrase, this user may never discover the on-line Thesaurus.

The TTS (RealSpeak by Nuance) is reasonable quality by today’s standards.

Kindle can only play uploaded music in the order in which files were uploaded.

Judging from the "Content sources" table in Wikipedia, the only source from which to buy Kindle books is the 4-500.000 book strong Amazon Kindle store. The primary source of free books is ManyBooks.net, which offers Kindle-formatted books at its nice website. Other than that, there isn't much because, even if gigantic World Public Library offers 750.000 books and documents in PDF format for an almost symbolic membership fee, and even though Kindle 2.3 is .PDF-native, the library's books typically seem to hold two book pages per PDF page, and that's simply too small to read on a 6" Kindle.

Here's a summary of Kindle 2's usability, applying the notion of usability presented in Multimodal Usability.

| Kindle 2 usability | |

|---|---|

| Technical quality | Does Kindle work? |

| General | Yes, Kindle works well in friendly day-to-day use. |

| Functionality | Can Kindle do the things you want to do? |

| General | Kindle is neither based on a well-defined set of user tasks, nor on the needs and preferences of a well-defined target user group or several, nor on a well-defined technological vision. Kindle functionality is a somewhat haphazard fistful of domain-relevant functionality some of which is mature and other is primitive. |

| The passionate reader | Perhaps the best fitting user group is that of incarnated (quasi-) text-only readers. They might prefer to switch the keyboard for a correspondingly larger display and drop music center, browser, text search and note-taking. |

| Simple web browsing | Browsing is unavailable in some countries with full GSM/3G coverage, such as Denmark, "due to local restrictions" says the error message but it is not clear what that means. |

| MP3 functionality | The music list order is fixed and cumbersome to revise. |

| Ease of use | Can you manage to use the Kindle? |

| General | Kindle is reasonably thumbable in its upright position and good to read text from. The GUI (Graphical User Interface) is only partially intuitive, and there are particular issues about device handling, non-text graphics output and text navigation. |

| GUI issues | Kindle has its limited share of classical GUI non-intuitiveness: a couple of ambiguous key labels (Aa, "enter" image icon), an ambiguous button (HOME), two multifunction keys (top edge switch, 5-way controller), numerous shortcut key combinations (explained in the manual). The context-dependent menus are relatively explicit and cover much (but not all) of the ground they should, often using short sentences ("Add a Note or Highlight") which may in many cases be clear to many of the users. |

| Learn to hold | Readers must get used to refraining from grasping the plastic frame in order not to push buttons accidentally. |

| Non-text graphics output | Enlargement of images, graphs etc. is cumbersome but often necessary and sometimes insufficient because the graphics are still too small, the in-graphics text too hard to read, the complexity too great, or the background greytone too dark, offering too little contrast. |

| Haptic input | The small-keyboard keys, buttons and 5-way controller fit a pair of thumbs rather well. |

| Navigating text | It is slow and cumbersome to navigate the text looking for a particular section or passage, non-text graphics, or even chapter headings (some books only). |

| Visual impairment | The visually impaired only need to push the Text Key and then nudge the 5-way controller to customise font size, words per line and text-to-speech except for audio volume. |

| User experience | How is the experience of using the Kindle? |

| Pleasure | Kindle is quite pleasant to hold loosely in a pair of hands and to read for hours as long as the material is text-only, like most novels and conservative neswspapers, and as long as one doesn't have to do multiple look-arounds for particular text passages and sections. |

| Tunnel view | Is restricted due to the small page size, which makes reading a text-only newspaper a very different experience from reading the paper-based version: you choose your article from a hierarchical menu, get it and read it. |

| Relaxing | Given the habit of turning Whispernet off unless in use, Kindle gives the safe impression of lasting weeks before the battery needs re-charging. |

| Comfort | It's great comfort to know that, in large parts of the world, new reading material is only a minute away - plus the time it takes to locate and decide what to purchase or what to select among the books that are available for free. |

| Uncertainty | Amazon "owns you" because the books you buy from them must be in Amazon's proprietary format AZW which, moreover, cannot be read on other e-book readers and is not being used by libraries. So it's easy to imagine one's investment in a Kindle dwindle in the future. |

We have seen that Kindle is a usable but not perfect e-book reader for reading novels and other sparsely illustrated content. It is relatively straightforward to infer a number of key requirements to an e-book reader of this kind that would be preferable to 6" Kindle 2.3. This Kindle is still a market leader of its kind but there is plenty of room for improvement.